In the country's chicken processing capital, undocumented immigrants live in fear

(This story was originally published Nov 25, 2017. It was awarded an Emmy on Oct 1, 2018.)

Across the United States, law enforcement officials from 55 counties collaborate with the federal U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE) to look for undocumented immigrants. Among them is Hall County, Georgia, whose main city of Gainesville has the largest percentage of undocumented immigrants in the country.

Since 2011, the Hall County Sheriff’s Office has turned over 2,000 people to ICE for deportation.

Univision recently visited Gainesville to find out exactly how immigrants here live, what they think of the current situation, what their fears are, how informed they are about their legal options in the country, and what they expect in the future. This is the first report of a project we call “Immigration Lab.”

Fear in the land of Trump

In Gainesville, located about an hour’s drive northeast of Atlanta, some 60% of immigrants lack legal immigration documents, according to estimates by the Pew Research Center.

Gainesville is the largest city in Hall County, one of four counties in Georgia that cooperate with the Department of Homeland Security to report the arrests of undocumented immigrants.

This is Republican terrain, and a Democrat hasn’t won the presidential vote here since 1980. Last November, Trump won easily here with 72.7% of the vote.

With the change in administration and the year’s first raids, fear began to overtake Gainesville’s immigrants, who are mostly Mexican. Many of them stopped driving, afraid that a traffic stop – however minor – could end in deportation.

In response, some supermarkets now offer free transportation to allow shoppers to buy groceries without having to drive. Taxi companies, almost all with Hispanic names (La Ley de La Vida, La Nueva Tijuana, Los Potros Taxi, El Sol, Solitarios and El Palmar, among others), increased the number of vehicles in their fleets to shuttle people to their jobs or to the supermarket. Six years ago, Hall County had six taxi companies. Today, there are 17, according to Georgia’s Department of Public Safety.

The fear is palpable among children, who leave home wondering if their parents will be there when they get back. “We have children who ask questions that we can’t answer: What’s going to happen to my mom? What will happen to my dad?" said Breana Wilson, who runs a local Boys & Girls Club in Gainesville. The clubs offer youth development programs, and almost half of their members in Gainesville are Latinos. They aren’t entirely aware of what’s going on with the different policies ordered by our president. It’s very difficult.”

“People stopped going to church because they’re scared," said Jaime Barona, a priest at St. Michael’s Catholic Church. "Children often don’t go to school because they don’t know if their father will return home, or their mother. There’s a terror that is real."

The Llantas Castillo tire shop provides a glimpse at the impact this fear can have on local business. The shop is located along the Atlanta Highway, along with most of the other Latino businesses in the area. Before Trump took office, four people worked at the tire shop. Two months into the administration, there were only two, and sales had dropped by nearly 80%.

“People who used to frequent our shop are leaving their cars at home because they’re too afraid to drive," the shop’s manager, José, said. "They no longer buy used tires. There was a day last February when we only sold $7."

No options

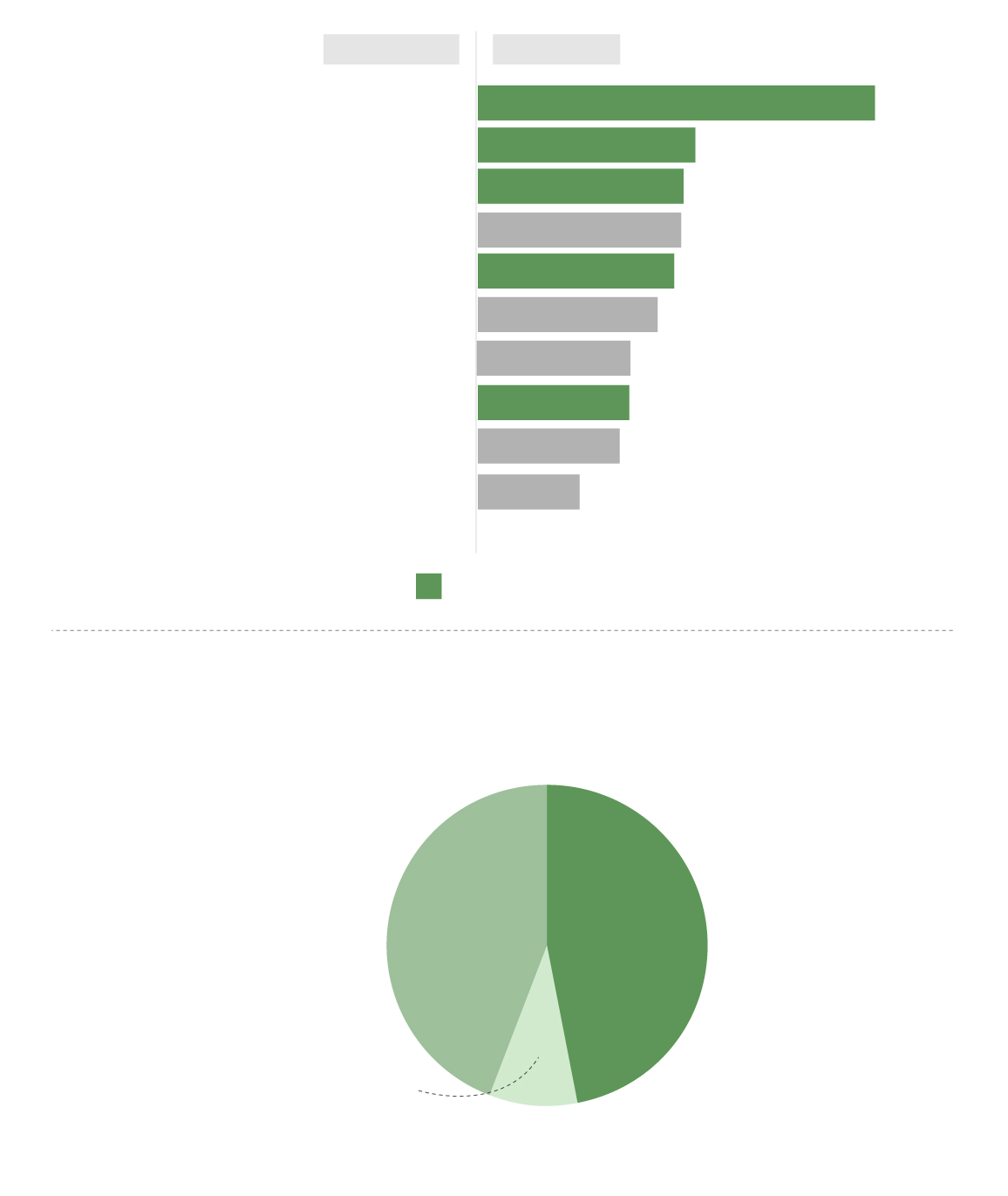

Gainesville is known as the poultry capital of the United States due to the large number of farms and processing plants operating in the city and its surroundings. Of the 10 industries with the most employees in the region, five are poultry processing plants that employ a total of nearly 8,000 people.

The poultry industry drives the economy

Five of the 10 main industries in Gainesville are poultry processing plants.

Companies

Employees

Fieldale Farms

2,550

1,390

Pilgrims

1,310

Victory Processing

1,300

Kubota

1,250

Mar-Jac Poultry

1,150

ZF Gainesville

990

Cottrell

970

Gold Creek Foods

900

Mars Wrigley

650

King’s Hawaiian

Poultry (chicken)

Georgia’s agricultural sector is dominated

by the poultry industry, which contribute

$838 billion to the state’s economy.

47%

44%

Dairy

cattle

Poultry

(chicken)

9%

Crops

Companies

Employees

2,550

Fieldale Farms

1,390

Pilgrims

1,310

Victory Processing

1,300

Kubota

1,250

Mar-Jac Poultry

1,150

ZF Gainesville

990

Cottrell

970

Gold Creek Foods

900

Mars Wrigley

King’s Hawaiian

650

Poultry (chicken)

Georgia’s agricultural sector is dominated

by the poultry industry, which contribute

$838 billion to the state’s economy.

47%

44%

Dairy

cattle

Poultry

(chicken)

9%

Crops

Companies

Employees

Fieldale Farms

2,550

Pilgrims

1,390

Victory Processing

1,310

1,300

Kubota

Mar-Jac Poultry

1,250

ZF Gainesville

1,150

Cottrell

990

970

Gold Creek Foods

900

Mars Wrigley

650

King’s Hawaiian

Poultry (chicken)

Georgia’s agricultural sector is dominated by the poultry industry,

which contributes $838 billion to the state’s economy.

47%

44%

Poultry

(chicken)

Dairy

cattle

9%

Crops

Companies

Employees

Georgia’s agricultural sector is dominated

by the poultry industry, which contributes

$838 billion to the state’s economy.

Fieldale Farms

2,550

Pilgrims

1,390

Victory Processing

1,310

Kubota

1,300

1,250

Mar-Jac Poultry

1,150

ZF Gainesville

47%

44%

Poultry

(chicken)

Dairy

cattle

Cottrell

990

Gold Creek Foods

970

Mars Wrigley

900

650

9%

King’s Hawaiian

Crops

Poultry (chicken)

Fuente: Greater Hall Chamber of Commerce | Univision Data

This industry largely depends on foreign labor. Local leaders estimate that 80% of Gainesville’s immigrants work cutting and packing chicken. And while few will say so out loud, most don’t have immigration documents.

Pedro, a 34-year-old from Guerrero, Mexico, who asked that his last name not be published, earns his living at a poultry processing plant. He has three daughters, all born in the U.S. Pedro says he is terrified every time he gets behind the wheel, but that he has no other choice.

When Univision News visited him at his home last March, Pedro’s youngest daughter was bedridden, diagnosed with Gaucher’s disease type 2, a congenital illness that kept her in an Atlanta hospital most of the time. Pedro and his wife traveled to the hospital most afternoons after work to be with their daughter. While his wife watched over the couple’s daughter, he would take care of his other daughters. He used to leave them at a neighbor’s home in the mornings before work, and pick them up in the afternoon to take them to visit their sister in the hospital.

“I leave my home, but really I don’t know if I’m going to make it back. It’s sad, and I can’t even imagine what would happen if one day the police stop me and take me in, what would happen to my family, what would happen to my baby, who is practically dying,” Pedro said.

Pedro’s daughter died in July, before her second birthday.

Like Pedro, many undocumented immigrants in Gainesville fear a run-in with the police that would land them in detention for driving without a license. That could get them deported.

In 2008, then county sheriff Steve Cronick signed an agreement known as 287(g) that governs the department’s collaboration with immigration officials. The agreement allows sheriff’s deputies to check the immigration status of those arrested for any type of violation, to register those who are undocumented for possible deportation, and to keep them in detention until “la migra” – immigration agents – come to pick them up. Ultimately, it’s up to the federal government to decide whether or not to take them into custody.

Since 2011, through this cooperation agreement, Hall County has processed 5,717 immigrants. Of those, 1,985 were turned over to agents from the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, or ICE, according to the sheriff’s office.

Until June of last year, the county jail had processed 218 undocumented immigrants – 177 men and 41 women – according to the sheriff’s office.

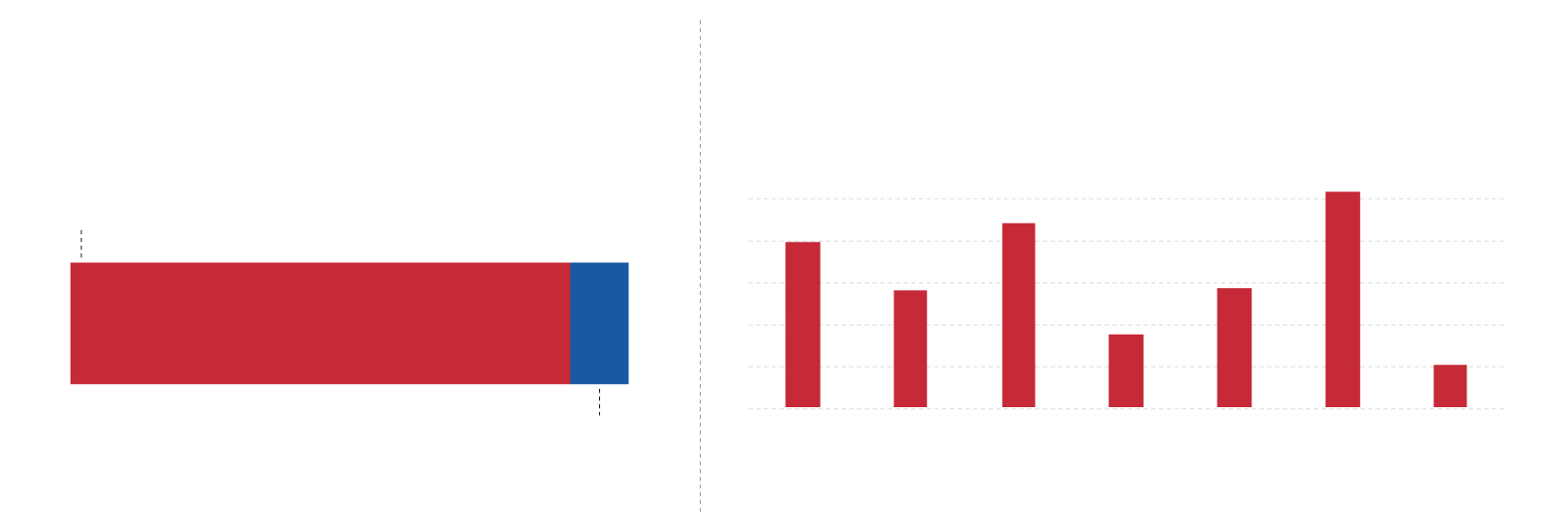

More arrests, fewer deported

In recent years, the number of immigrants arrested in Hall County has increased. But the number of people ICE removes continues to decrease.

Source: Hall County | Univision Data

In June 2016, Sheriff Gerard Couch renewed the agreement. His justification was similar to Donald Trump's: Couch said he’s targeting drug dealers and gang members for removal from the country.

“We have a very large Hispanic population. A large immigrant population. And we had an increase in crimes against people from the community. … The 287(g) program focuses on those individuals who come here to take advantage of others – drug dealers, gang members, those who commit violent crimes, and those who are appropriate for deportation from this country, from this community,” Couch told Univision News.

Couch cited a drop in crime in Hall County in recent years as justification for the need for the program to continue.

But while crime may be decreasing, the figures he cited aren’t exceptional. Crime has dropped in nearly all of Georgia, including in neighboring counties that didn’t sign onto the 287(g) program. In general, the U.S. has seen a decrease in crime in recent years.

A closer look at the figures shows that Gainesville actually experienced a smaller decrease in aggravated assault than overall in Georgia. Most violent crimes, such as sexual assault and homicide, actually increased in frequency in recent years.

Exceptional actions, similar results

The Hall County sheriff says that the 287(g) program has reduced local crime. But crime trends are nearly equal across the state. These graphics show this reality with crime rates for each 10,000 inhabitants.

Source: Georgia Bureau of Investigation | Univision Data

From sheriff’s deputy to activist

One of the biggest critics of 287(g) is Anmarie Martin, a Puerto Rican activist who worked in the Hall County Sheriff’s Department for nine years and became a sergeant. Martin was one of the officers trained under the 287(g) program. She resigned in 2014 because of what she saw while on the job.

“The training tells you that you are going to lock up and process people who are criminals, but in this case, 287(g) is meant to destroy people," she said. "Arresting a human being who is working to feed their family, turning them into a criminal, and removing from that family unit is inhumane. My uniform became a burden. I no longer felt proud serving my country. My resignation was immediate.”

Martin specifically remembers the case of a man who was sent to immigration authorities after being detained for fishing without a license.

“I’m never going to forget that. It sparked an internal struggle inside of me. How is it possible that I’ve taken an oath to protect and serve, yet at the same time I’m destroying families? I couldn’t continue. I publicly refused to apply the law, and that’s when my career at the sheriff’s office came to an end,” she told Univision News.

After her resignation, Martin founded an organization called Upload Humanity, which provides legal assistance to families of immigrants and support during deportation cases.

She says that the discourse that associates immigrants with crime is wrong. “The majority of serious crimes in this country are committed by U.S. citizens. This rhetoric that they’re selling us through Safe Communities to enforce 287(g), not only in Georgia, but in all of the United States, is a fallacy.”

The numbers seem to support her statements. Of 536 criminal charges that were filed against immigrants who were processed under the 287(g) agreement in Hall County in the first six months of this year, 70% were for traffic violations unrelated to driving under the influence of some type of substance.

Two law enforcement agencies, one jail

Local police in Gainesville don’t have the resources to implement the 287(g) agreement, and only the sheriff’s department is authorized to do so. But many immigrants don’t make this distinction, so they fear both police departments equally.

As a result, local police officials fear that immigrants will stop reporting crimes in order to avoid interacting with officers. “If you’ve been a victim of a crime, don’t be afraid to call the police. We’re not here to detain you. We’re not ICE agents. That’s not our job,” officer Joseph G. Britte Jr. said.

Local police have tried to build a closer relationship with the community by speaking at churches or circulating surveys in Spanish.

But the fear felt by immigrants is warranted, because Gainesville has only one jail: the county jail, operated by the sheriff’s department. That’s where anyone detained by local police ends up, regardless of the crime committed. Once there, sheriff’s deputies can process people based on their immigration status.

Some Hall County deputies say that they confront dilemmas daily even though their mandate isn’t to look for undocumented immigrants. Should they detain someone who is driving without a license, which is a crime, or let them go?

“My goal isn’t to come to work to look for undocumented people and take them to jail for any reason. People are here to take care of their families. So, they have to go to work. And that’s why they’re driving. But you have to have a driver’s license to operate a vehicle. You could be issued a fine or you could end up in jail,” officer Ryan Daly said during a recent patrol of the county, during which he was accompanied by a team from Univision News.

For businesses, a contradiction

There's another contradiction in Gainesville: Georgia’s poultry industry supports Trump, who accuses immigrants of stealing jobs from U.S. citizens. These companies seem to be supporting the main oppressor of their own employees.

Working at the processing plants is a difficult job, and many “Americans” don’t want to do it, company owners admit. Because of this, much of the industry depends on foreigners – mostly Mexicans – who began arriving in the area in the 1980s, reaching their height in 2004, according to Tom Hensley, president of Fieldale Farms, Gainesville’s biggest poultry industry employer.

Fieldale Farms is headquartered in the nearby town of Baldwin. The company processes about 3 million chickens a week that are sold in restaurants and supermarkets across the country. Its Murrayville plant alone employs 1,700 foreign workers who speak a total of 13 languages.

Drastic anti-immigrant measures in recent years have forced many of them away. The company must constantly search for new workers, as demonstrated by an ad on its website.

“Just in the last year the available workforce has declined. I miss those young Mexicans. They were good workers. The people we have now, we love them and they do a very good job. But when you’re 50, you can’t work as hard as you could when you’re 20,” Hensley said.

Despite this, Hensley admits that he voted for Donald Trump hoping that his industry would be freed from government controls and inspections, which he says are excessive. His company donated to Trump’s campaign. Since 2002, Fieldale Farms has donated more than $500,000 to Republican candidates for the state Senate, U.S. Congress and president.

“You know, to be honest, what I did was to vote against Hillary Clinton. Because she would have continued the mounting regulations of President Obama. We’re overregulated. In our small business we have meat inspectors. All meat must be inspected. And they do a good job, but we also have OSHA [the Occupational Safety and Health Administration], we have the EPA [the Environmental Protection Agency], we have the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, we have the Department of Labor,” Hensley said.

Business comes first

Fieldale Farms is the main private employer in Gainesville. It depends on foreign workers. But it also supports the Republican Party and Donald Trump.

Donations from Fieldale Farms

since 1990

$95,362 Contributions to Democrats

$824,050 Contributions to Republicans

Contributions to the Republican Party

since 2004

$102,600

$87,900

$78,750

$56,850

$55,650

$34,800

$19,900

2012

2004

2006

2008

2010

2014

2016

Donations from Fieldale Farms

since 1990

$95,362 Contributions to Democrats

$824,050 Contributions to Republicans

Contributions to the Republican Party

since 2004

$102,600

$87,900

$78,750

$56,850

$55,650

$34,800

$19,900

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

Contributions to the Republican Party

since 2004

Donations from Fieldale Farms

since 1990t

$102,600

$824,050 Contributions to Republicans

$87,900

$78,750

$56,850

$55,650

$34,800

$19,900

$95,362 Contributions to Democrats

2012

2004

2006

2008

2010

2014

2016

Donations from Fieldale Farms since 1990

Contributions to the Republican Party since 2004

$102,600

$87,900

$824,050 Contributions to Republicans

$78,750

$56,850

$55,650

$34,800

$19,900

$95,362 Contributions to Democrats

2010

2012

2004

2006

2008

2014

2016

Fuente: Open Secrets | Univision Data

Hensley believes that the U.S. should implement a broad labor program to allow more foreigners into the country to do the work that U.S. workers won’t.

“When President Bush was in the White House we were very close, but it didn’t happen,” he said.

It's even less likely under Trump, considering that the administration wants to cut legal immigration in half.

Trying to live a normal life

Caught in the middle of these contradictions, Gainesville’s immigrants struggle to live life with a sense of normalcy. Juanita, 43, who asked that her last name not be published, was born in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, and has lived in the U.S. since 1994. Although she was married to a U.S. citizen who is the father of her three children, she hasn’t been able to get a green card. For the past six years, she has worked in a pollera, or poultry processing plant, earning $12.50 an hour.

At the beginning of the year, Juanita was arrested for driving without a license. She spent a night in the county jail, where she was registered as undocumented. She still doesn’t know how she was released without immigration authorities coming for her.

One of the tools that Juanita and other Gainesville immigrants use to avoid being caught is a WhatsApp messenger service that alerts users to police checkpoints on the highways. She subscribed to the service after a friend recommended it, but she doesn’t know where the information comes from or if it’s reliable.

“We undocumented immigrants are desperate, worried and sad. There’s no way for us to obtain permission. The gringos say we come here to steal their jobs, but that’s not true. We Latinos are harder workers,” she said.

But now she’s scared. She pays a taxi to take her to work, to the supermarket, or to dance Zumba, her favorite activity and one that allows her to feel she's living a normal life. The hidden locale where Juanita exercises twice a week is run by Antonia and María Yeini, two undocumented Mexicans who started their business three years ago to help Latinas in the community stay healthy.

Dozens of women gather there, mainly in the afternoons, to dance, drink milkshakes and socialize. It allows them to release their constant stress.

That fear also affected the business. Last March, Luna and Yeini canceled the first class of the day, at 5 a.m., because their clients no longer wanted to go out at that quiet hour.

Despite the fear of being arrested and deported, many continue to leave their homes every day to work or drop off their kids at school. Like Pedro, they have no other choice but to drive without a license while avoiding police who say they are out looking for criminals.